A brief history of Broken Hill from the Papers of the Centre

Murshid F. A. Ali ElSenossi

"Then

there came running, from the farthest part of the City, a man, saying,

'O my people! Obey the Messengers:

Obey those who ask no reward of you (for themselves), and who have

themselves received Guidance.

It would not be reasonable of me if I did not serve Him Who created

me, and to Whom you shall (all) be brought back'."

(Holy Qur'an 36:20-22)

"Beyond the Darling River on the edge of the sundown, is where

they used to say you would find Broken Hill, as if there was nowhere

further to travel in Australia. Perhaps it was the feeling of suddenly

being confronted by such vast space, like an inland sea rolling into

the sunset.

The desolate landscape surrounding the town is like driving towards

a painting of soft mauve and sage hues. Is it any wonder the city

has become known as a 'mecca' for artists? It is here that the magnificent

clear blue skies and the magic light are also much loved by film makers.

It is here that the big red roos run two hundred kilometres in a night

chasing a thunderstorm, and the unique Sturt Desert Peas bloom in

dark red soils."

Did you know?

The City of Broken Hill is the largest regional centre in the western

half of New South Wales.

It lies in the centre of the sparsely settled New South Wales Outback,

close to the South Australian border and midway between the Queensland

and Victorian borders.

The nearest large population centre is Mildura in Victoria, three

hundred kilometres distant to the south on the Murray River.

The nearest large city is Adelaide, capital of South Australia, approximately

500 kilometres to the southwest.

Because of its location Broken Hill has strong cultural and historical

connections with South Australia and operates on Central Australian

Time, one half hour behind Eastern Standard Time ". (Broken Hill

City Council - Profile www.brokenhill.nsw.gov.au)

The term 'Broken Hill' was first used by the early British Explorer

Charles Sturt in his diaries during his search for an inland sea in

1844. Western plains towns far away from the major rivers, such as

Broken Hill, owe their existence to the mineral discoveries made in

the decade after 1875, when spectacular deposits of gold, silver,

copper and opal were found.

The township of Broken Hill was developed in the "Broken Hill

Paddock" which was part of Mt. Gipps Station. George McCulloch,

the station manager, employed many men; and it was in 1883 that three

of his workers pegged the first mineral lease on his property; they

were Charles Rasp, David James and James Poole. (Drewery, 1985 &

Camilleri, 2009). These men, along with four others formed the 'Syndicate

of Seven' later that year. They were the original members of the Broken

Hill Mining Company formed in 1883, who lodged applications for mining

leases along the Line of Lode.

The members, who all worked at Mount Gipps Station, were:-

1. George

McCulloch (1848-1907)-Station manager.

2. Charles Rasp (1846-1907)-Boundary rider.

3. Philip Charley (1863-1937)-Sheep farmer, employed as a boundary

rider.

4. David James (1854-1926)-Tank and fencing contractor.

5. James Poole (1848-1924)-Employee of David James.

6. George Urquhart (1845-1915)-Bookkeeper and overseer

7. George Lind (1861-1941)-Storekeeper.

Each member

paid £70 to be a member of the Syndicate and in September 1883

they pegged seven 40 acre blocks along the Lode. The initial results

were not encouraging and Poole, Urquhart and Lind sold their shares

before the boom days and flotation of Broken Hill Proprietary (now

known as BHP) in 1885. These men pegged out the remaining six mineral

leases which are known as the Line of Lode. It was the seventh member

of the Syndicate, Philip Charley, who found the first amount of silver

in 1885 .(Drewery, 1985 & Camilerri, 2009). A township was soon

surveyed and Broken Hill was initially a shanty town with an entire

suburb named 'Canvas Town' for its temporary buildings. Today, the

'Line of Lode' is a 30 metre high mullock heap that bisects Broken

Hill. The Visitor's Centre, Miners Memorial and Broken Earth Café

perch atop this unmistakable landmark.

Aboriginal

history of the area

There were some fifteen groups of Aboriginal people traditionally

living in the huge area bisected by the Darling River in the western

plains of NSW. The principal group around Broken Hill was the Wiljakali

Tribe. Their occupation of the area is thought to have been intermittent

due to the scarcity of water. The same scarcity of water made the

area unattractive for European occupiers, and traditional Aboriginal

ways of life continued longer there than in many other parts of NSW,

into the 1870s. However, mobility was essential to life in the mallee

and sand hills, and as Aboriginal people were increasingly deprived

of the full range of their traditional options, they were obliged

to come into stations or missions in times of drought to avoid starvation.

By the 1880s traditional lifestyles were largely supplanted by mission

lifestyles, with many Aboriginal people also working on stations or

within the mining industry. With the failure of most of the stations

during the 1890s depression, many local Aboriginal groups were again

displaced and ended up living in reservations created under the Aborigines'

Protection Act of 1909. The influenza epidemic of 1919 had a further

significant impact upon the indigenous population(HO, 1996, 192-193.)

as did the twentieth century federal government policy of removing

Aboriginal children from their families.

The Line of Lode and the Miner's Memorial

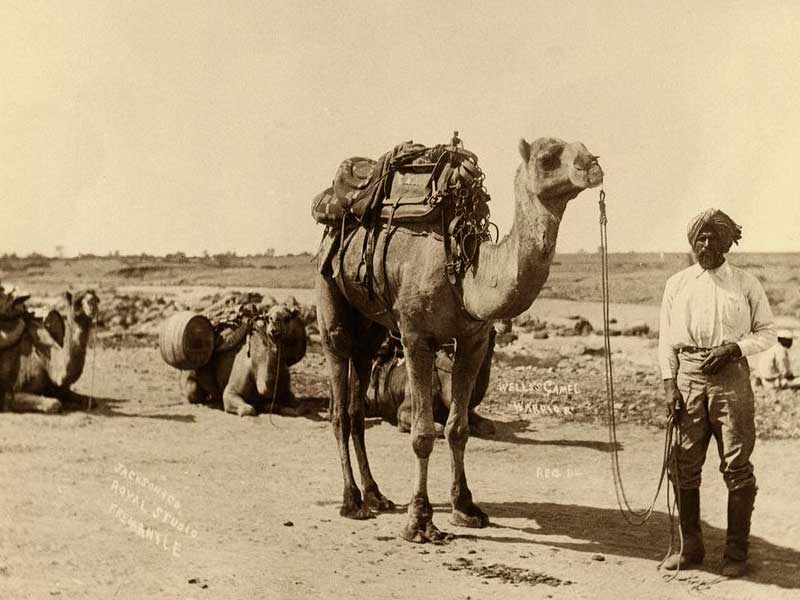

Cameleering

history in Australia and Broken Hill

Camel drivers led hundreds of camel trains throughout inland Australia

in the nineteenth century and by the turn of the twentieth century

their camel trains provided transport for almost every major inland

development project. The cameleers laboured across the continent,

carting produce, water, mail and equipment at a time when roads and

railways were not constructed. The indomitable camels and their equally

hardy keepers were crucial to momentous projects such as the construction

of the Overland Telegraph, for which they carried supplies and materials

used in surveying and construction work. They also accompanied a number

of exploration parties into the little-known interior. These early

Cameleers contributed greatly to the development of rural and remote

Australia (Powerhouse Museum, 2008 & National Archives of Australia,

2007).

It is estimated that some 20,000 camels were brought to Australia

during the second half of the nineteenth century from all different

parts of the world to work in the vast areas of inland Australia.

Their drivers came from different countries and provinces such as

Kashmir, Sind, Rajasthan, Egypt, Persia, Turkey, Punjab, Baluchistan,

and former provinces of Afghanistan, now modern day India and Pakistan.

Collectively they were known as "Afghans," although very

few were actually of Afghani descent, it is now widely (and subjectively)

used to describe the Cameleers (Australian Government: Culture Portal,

2009 & Camilleri 2009).

The Afghans were of the Islamic faith and practising Muslims; they

introduced their culture, customs and religion to NSW and also brought

a varied vocabulary of terms to Australia. The only word that found

a place in the Australian language was the command "hooshta",

which ordered the camel to kneel or rise. The Australian equivalent

is the word 'hoosh' or 'whoosh' which was universally used by cameleers

(Powerhouse Museum, 2008)

.

The forerunners of the camels to enter the Broken Hill district were

imported in 1866 by Sir Thomas Elder for use in Northern South Australia.

The Afghans, or Ghans as they became known, were well established

by the time of Broken Hill's discovery in 1883 and in succeeding years,

camel teams and Afghans were a familiar sight in Broken Hill and the

West Darling District of NSW. Camels were used to haul heavy wagons,

and twelve or more camels were used to pull a ten ton wagon travelling

at a rate at 15 miles per day (Powerhouse Museum, 2008).

Once camp was reached the Afghans slept in a temporary corrugated-iron

shed or bower of gum branches. They led a nomadic life with few personal

possessions. The Afghans generally lived away from white populations,

at first in makeshift camel camps, and later in Ghan towns on the

edges of existing settlements(Powerhouse Museum, 2008). For most of

the year they were solitary travellers lacking the camaraderie and

powerful sense of community or 'Ummah' that Islam bestows. The Afghans

performed their prayers five times daily out in the desert, the empty

bushland, or countryside. In Islam great emphasis is placed on the

conduct of prayer. Salat can be performed at any clean place ensuring

that the worshipper is directed towards the Ka'aba in Mecca. A mosque,

which is referred to in Arabic as a 'Masjid,' lit. 'Place of prostration',

is a dedicated place of worship. It is a place to gather for daily

prayers and festivals, and a place where the community come together

for spiritual advancement, through prayers and remembrance and through

religious education. A mosque can also be a reference point for other

community activities. Mosques should remain an Islamic endowment (waqf)

which is owned and looked after by the Muslim community.

Over the following four decades, the Afghans and their camels were

to play a crucial role in almost all subsequent exploratory expeditions

and scientific survey parties in the outback. Afghans were consequently

among the first non-Aboriginals to view such iconic landmarks of central

Australia, such as Kata Tjuta and Uluru, and had their own names ascribed

along the way to places such as Allanah's Hill and Kamran's Well as

the explorers mapped the emerging geography they traversed (Scriver,

2004)

.

Within just six years of the arrival of Elder's first camels, and

just a decade after Burke and Wills' first north-south crossing of

the continent, the Afghans with their camels had built the overland

telegraph from Adelaide through to Darwin that would connect Australia

direct to London. The construction of railways was shortly to follow

including the Afghan's namesake, the famous Ghan line from Port Augusta

to Alice Springs. The Ghan service's name is an abbreviated version

of its previous nickname 'The Afghan Express,' which comes from the

Afghans that trekked the same route as the overland telegraph, which

is said to have been the to be the route taken by John McDouall Stuart

during his 1862 crossing of Australia before the advent of the railway

(Burton, 2006).

The Afghans travelled lightly and were always ready to move. The men

were typically engaged on limited term contracts, and immigration

laws did not allow for women or children to accompany them to Australia.

Many therefore worked and lived communally as a brotherhood of fellow

cameleers, observing strict religious and related halal dietary practices

that tended to discourage significant social interaction with others.

Theirs was an itinerate mode of dwelling negotiated spatially through

movement, camping along the camel trails, resting between journeys

in their Ghan towns (Scriver, 2004).

Broken Hill was a central hub at which several important camel trails

and stock droving routes of the outback met the railroad and became

a prominent place of commercial interaction between Afghans and Europeans.

With its high concentration of Afghans, the camp at Broken Hill developed

as one of the most established Ghan towns of the outback (Camilleri,

2009).

The Ghan town along with the dwellings of the local Aboriginal people

were rarely located near the centre of town, which clearly segregated

the whites from the 'others'. Essentially in towns where the Afghans

worked there were three groups, a camp for the Afghans, a camp for

the local Aboriginal people and, in town was where the Europeans lived.

Despite the cameleers' historical and instrumental role in the development

of NSW, the lack of substantive material and proprietary claims to

'place' on the part of most of these men denied them recognition as

a constituent community within the emerging cultural fabric of the

new nation. Along with Aboriginal people, the Afghans experienced

racial discrimination and both spatial and economic marginalisation

in the Australia of the early twentieth-century (Scriver, 2004). Labour

unions representing the powerful lobby of white teamsters had long

orchestrated racist antagonism against the Afghans in an unsuccessful

bid to exclude them and their camels from the transport business.

But once the teamsters began to replace their horses with motorised

vehicles, the competitive advantage of camels was rapidly overcome.

By the time of the First World War, there was little place or purpose

remaining for the camels and the Afghans within NSW (Scriver, 2004).

Out-of-work cameleers were compelled to come in from the bush and

shift into other forms of employment wherever they could find it.

Many became hawkers and day labourers, eking out a living in the margins

of larger urban settlements such as Adelaide and Broken Hill.

Following the war, camel transport was finally eclipsed in Australia.

In due course the Afghan cameleers substantially vanished. Some returned

to Afghanistan or resettled in the new Islamic state of Pakistan that

emerged. Most Afghans who came to Australia were single or if married

left their wives behind as they expected to return wealthy. Many remained

single; others married Aboriginal women and a few married European

women. Those who took wives in Australia were ultimately assimilated,

according to the strict segregationist policies of the government,

into either the Aboriginal or European communities.

Even the Ghan towns-the only material places the Afghans had called

home-were gradually abandoned as they lost their economic base.

Afghan Mosque at Broken Hill, NSW

Broken Hill Mosque

Australia's first mosque was built at Maree in northern South Australia

in 1861, the first large mosque was built in Adelaide in 1890, and

the first mosque in NSW in Broken Hill in 1887. The mosque was originally

located at a camp in West Broken Hill and was relocated to its present

site about 1903-1904. It was constructed by the Afghans and comprises

a modest structure made from wood and corrugated iron sheeting, painted

rust red (which is the colour of the original mosque and a typical

colour of Broken Hill). The adjoining anteroom is also constructed

of the same materials. The mosque sits on a dusty site at the edge

of town, with an avenue of date palm trees, planted in 1965 by the

Broken Hill Historical Society. At the entrance of the site are two

olive trees which were planted by The Islamic Council of NSW in December

2008. Surrounding the mosque are original camel wagon wheels made

from wood and iron used by prominent Afghans in the town; mainly Shamroze

Khan and Poujen Khan. To the far eastern corner of the site is the

water trough used by the men to make their ablutions before they entered

the mosque. Upon removing their footwear the men stood beside the

concrete channel as water was poured over their feet and they entered

the mosque using specially constructed stepping stones which are now

housed in the adjoining museum.

The Afghan mosque and camp was described in 1955 by Colin Sayers of

Broken Hill in the 'Melbourne Age' as:

"Two

camps of teamsters on the sandy outskirts of the town, squalid collections

of rusty corrugated iron and hessian humpies. They were at most two

roomed dwellings . . . narrow, rutted lines bisected the huts. There

was a stone built mosque in a small, sandy square, its low minaret

scantily shaded by a dusty pepper tree. They were picturesquely squalid

characters, known popularly among us in boyhood years as "hooshtas"

from the command they gave the camels... All of them wore turbans

and long baggy white cotton trousers. Sunday mornings we visited the

"Ghan" camps...Children in large number played in the dust

at the doors of the huts..." (Solomon, 1988).

The men, particularly the older and more devout Muslims, went to the

mosque regularly; especially on Friday which is the traditional Muslim

day of gathering. Some Afghans would not work on a Friday between

noon and 2 pm. A mosque attendant would call the men to prayer by

singing out loudly from the mosque's grounds. One Broken Hill Afghan

descendant, Abdul Fazulla, could recall seeing such a person, Mohamed

Raffeeg, standing on the cement outside the mosque, putting his hands

cupped with palms outward to the side of his face and making the call

to prayer. His voice travelled over the camp to the Ghan town at the

north end of Chapple Street (Rajkowski, 1987). If the devotees were

not near a mosque for the morning or evening prayers, they would pray

wherever they were. Many old-timers from Broken Hill recall seeing

Afghans in the bush working with their camel trains, stopping mid

way at a certain time, kneeling on their mats praying (Rajkowski,

1987).

The mosque was well used even when the Ghan community diminished in

later years and the few Muslims remaining in Broken Hill continued

to use it regularly up till 1940 and then less frequently until the

death of the last Mullah in the 1950's. After his death the mosque

fell into disuse and was vandalised.

Dost Mahomet was a prominent Afghan Camel driver who worked at Broken

Hill. He arrived with the camels and later travelled part of the distance

and assisted the explorers. His grave lies three kilometres from Menindee,

on the road to Broken Hill, and is the first known Muslim person to

be buried on Australian soil (Matthews, 1997).

At present there are few descendants of the early Afghan families

in Broken Hill. The mosque has been renovated and refurnished by members

and friends of the Broken Hill Historical Society and the Islamic

Council of NSW to mark a unique but important phase in the development

of transport in the West Darling district of NSW.

Current history

The Broken Hill Mosque is located on the corner of 703 William Street

and 246 Buck Street, Broken Hill. However this is not the initial

site of the mosque. The Cameleers lived in two camps, one at North

Broken Hill, off the end of Chapple Street, and the other camp at

West Broken Hill on the corner of Kaolin and Brown Streets. There

was a small mosque at the west camp which was relocated when the area

was developed for houses and placed behind the mosque at the main

north camp.

The land upon which the Broken Hill Mosque currently sits was first

granted in 1891 as part of 'Portion 1940', bought by David (or Daniel)

Miller of Broken Hill (Hanna, 2009). In 1903 Miller sold the portion

to 'Afzul of Broken Hill, camel driver'. It fell to disrepair after

the death of Afzul, the last regularly practising Muslim and acting

Mullah. The land and mosque was then acquired by his son, Abdul Fazulla

of Broken Hill, a truck carrier/labourer in 1961 (Hanna, 2009).

After Council had acquired the title to the block for non payment

of rates, it was renovated and refurnished by members and friends

of the Broken Hill Historical Society who are now its trustees. In

September 1968 it was officially opened. The ceremony was attended

by the Towns Mayor and visitors from a mosque in Adelaide were invited

to worship and bless the site to show it be a sacred and Holy place

in NSW's Islamic community and culture. The mosque is one of the last

remaining remnants of "Afghan" immigration to NSW and embodies,

in built form, early Islamic culture in Australia which is otherwise

not so significantly represented in the State.

A small museum has been established in the anteroom of the mosque

for display of camel bells, nose pegs, photographs, the original stepping

stones, camel saddles, traditional female and male headgear from Baluchistan,

and in a glass showcase is a walking stick that belonged to the last

Mullah along with other items associated with the Islamic religion.

The museum is open to the public every Sunday from 2pm-4pm and can

be opened for worship on request.

References:

Broken Hill City Council: www.brokenhill.nsw.gov.au

Broken Hill Historical Society

H.M. Barker 1957 Camels and Afghans

Muslims in Australia from: (www.imamreza.net/eng/imamreza.php?id=3926)

A brief history of the Muslim Community in Australia (www.islamfortoday.com/australia.htm)

Jamila Hussain Islam its Law and Society - Chapter 15

National Archives of Australia, Muslim Journeys (www.uncommonlives.naa.gov.au/)

Peter Scriver,2004 Mosques, Ghantowns and Cameleers in the Settlement

History of Colonial Australia.

Rosamund Burton Dr. Anne Monsour and Paul Convy, 2006, Into the Red

New South Wales, www.news.com.au.

South Australian Museum, 2008, Australia's Muslim Cameleers- Pioneers

of the Inland 1860-1930, (http://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/page/default.asp?site=1&id=1561)

Zachariah Matthews, 1997, Origins of Islam in Australia (www.worldupdates.tripod.com/newupdates10/id17.htm)

Bill Seager, 2007, Australia's Muslim Cameleers: Pioneers of the Inland

Christine Adams , 2004, Sharing the Lode: the Broken Hill Migrant

Story

Christine Stevens, 1989, Tin Mosques and Ghantowns; A history of Afghan

Camel Drivers in Australia

H.M. Barker, 1972, Camels in the Outback

Jenny Camilleri -Presdident of the Broken Hill Historical Society

Inc, 2009, Personal communications with Patrica Assad at the Heritage

Branch.

Kevin Baker, 2006, Mutiny, Terrorism, riots and murder: A history

of sedition in Australia and New Zealand.

Powerhouse Museum, 2008, Powerhouse Museum Collection Search: Camel

Saddles

R.J. Solomon, 1988, The Richest lode: Broken Hill 1883-1988 .

Roberta J Drewery, 1985, Streets of History: naming our streets, Broken

Hill, NSW

Roberta J Drewery, 2008, Treks, Camps, and Camels: Afghan Cameleers

and their contribution to Australia.

Tom L. McKnight, 1969, The Camel in Australia Unpublished Report for

the Heritage Branch by Bronwyn Hanna 2009, Broken Hill Historical

Title Search

Almiraj Sufi & Islamic Study Centre, Inc.

Almiraj Sufi & Islamic Study Centre, Inc.